-

Pagoda, Beyond the Beauty

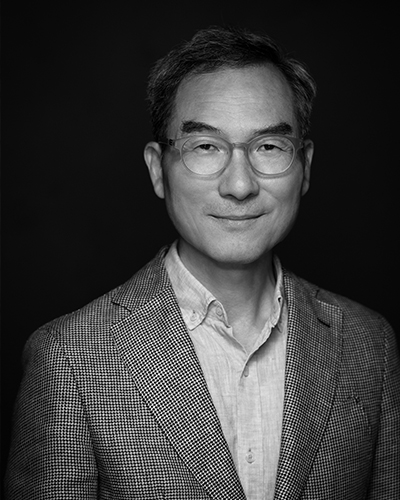

by Jason J. Kim

I was born in Korea, but I am currently living in New York. I have spent more of my life in New York than in Korea. New York is where I lead my daily life; Korea is a place that I would like to know better. I came across Yang Hyun-mo’s pagoda photographs in New York City in the winter of 2017. These pagodas, standing upright in perfect symmetry against a backdrop of black cloth, were different from the traditional images of pagodas that I was familiar with. I sensed something that the word beautiful did quite capture. I felt a certain force that made me take a closer look at the pagodas. I was not simply seduced by the beauty of the subject; I was gripped by a power within the images that demanded all my attention.

These photographs impelled me to meet the photographer. Yang Hyun-mo had been photographing pagodas around Korea since 2010. I asked him why he chose pagodas. I was curious what had guided him for nearly a decade. He told me that he had reached the limits of commercial art, photographing for the advertising and fashion industries. His skills were recognized, and he had achieved wealth and honor. But he felt that something was not quite right. One day, while traveling alone, he discovered pagodas, as though it were meant to be. Looking at a pagoda that had occupied the same space for over a millennium and received the prayers of countless people, he felt an indescribable excitement and joy rising in his heart. For a year after that, through spring, summer, autumn, and winter, he carried his camera up mountains all over the country to photograph pagodas. After ten years of following his volition, the artist has become one with the pagodas.

In conversation with Yang, I understood the force that had moved me and attracted me to the images. When I laid eyes on Yang’s pagodas, the prayers of countless people, their fervent, desperate emotions, transcended time and space and settled in my heart, leading me to rediscover my inner self projected on the pagodas.

Having encountered splendid photographs and their creator, I wanted to spread the word. I wanted to share and discuss what I felt. Story K was created to share beautiful stories of Korea. For its first story, Story K presents the pagoda series by photographer Yang Hyun-mo. All over Korea, these pagodas, Korean treasures, stood in one place, receiving prayers and wishes of countless people for over a thousand years. These treasures found Yang Hyun-mo and have been reborn as works of art. I hope that this exhibition will be about more than simple appreciation, providing an opportunity for meaningful self-reflection.

-

Photographing the House of Buddha

by Robert C. Morgan / American art critic, art historian, curator, poet, and artist

Hyun-Moh Yang received most of his education from Chung-Ang University in Seoul in the prestigious Department of Photography, which many consider to be the premiere university for photographic studies in Korea.

It was here that Mr.Yang became aware of the differences between fine art photography and photographic design. In addition to his laudable undergraduate and graduate training from Chung-Ang, Mr.Yang was also granted honors from the Instituto Italiano di Fotograpia in Milan that further consolidated his knowledge of technical, formal, and theoretical expertise.

While Yang is well versed in many areas and photography, much of his career in recent years has been devoted to working with leading design firms for which he is highly regarded in the field and very much in demand. Concurrent to his business, Mr. Yang has in recent years been involved in photographing pagodas that he has visited throughout Korea. A pagoda is a tiered tower associated primarily with Buddhism with multiple eaves or roofs, equidistantly placed in vertical succession to one another. The concept of the pagoda originated in India from the domed Stupa that represented a place of worship for Siddhartha Buddha.

The pagoda gradually evolved over time in China, and later in Korea and Japan, where the architecture of the pagoda appeared as a tomb structures that often contained sacred relics.

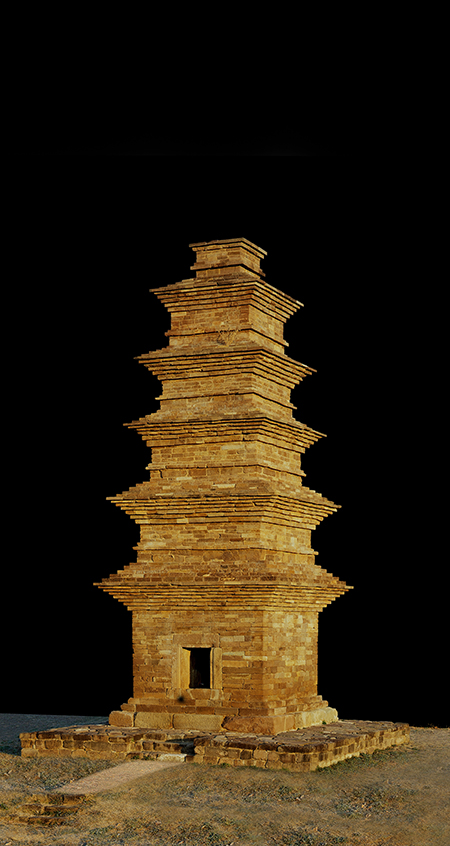

Yang’s method of photographing the pagodas? most of which were built in Korea during the so-called Common Era from the late Shila through the early Goryeo Dynasties? follows a technique frequently used in his commercial practice. This involved placing a neutral fabric background behind a fashion model or an object being photographed in order to focus the viewer’s concentration and thus avoid interference with extraneous surroundings. The Pagoda series representsn an example of Yang’s keen ability to bring together his knowledge of fine art with design.

In photographing the pagodas from Jeongnim-Sa and Bongam, for example, the background is entirely neutral due to the seamless presence of hanging black fabric that ‘erases’ the presence of a background. This is used throughout most of Yang’s Pagoda photographs in order to give the viewer a sense of focus and concentration. For Yang, it is not the religious aspects of the work that interests him, but the Korean sense of calm these structures emit. Once might say these structures of tarnished brick have a beauty of their own. Rather than being seen or read symbolically, the artist is interested in creating an open environment, a space and a place that lends itself to a meditation point of view rather than a strictly religious one.

Having met the artist, I was interested not only in the works involving the drapery behind the pagodas but also in some of the photographs in which the winter environment seemed to play an important role. To see one of these photographs, such as Pagoda Hwaeom-Sa, isolated in front of a natural black background is interesting, but so are the photographs of the pagodas seen in a natural environment covered in fresh snow at rest after an intense blizzard. Here the fallen snow on the eaves and the base of the pagoda also contain a message. This was made apparent to me upon first seeing a group of Yang’s random photographs.

The message was that nature fulfills the presence of the pagoda not so much in terms of its religious symbolism, but rather as a place as having its own spiritual presence. From Yang’s point of view the ‘spiritual presence’ of a pagoda ? whether in Korea, Japan, or China ? does not have to be interpreted only according to a religion. Rather there are moments when the spiritual power of the monument transcends its religiosity in order to become for the viewer an experience beyond the everyday material world. In this sense, the Pagoda photographs of Hyun-Moh Shaw go beyond preconceived boundaries of a particular religion. The experience one gets from these photographs may contain a multiplicity of religious ideas, whether they are Buddhist, Taoism, Catholic, or Confucian. They open the doors of a myriad of discursive ideas based on what each individual viewer sees and feels.

Another concern relative to Yang’s photographs is the notion of beauty. Where does it abide? And how do we interpret its meaning? Whereas commercial design tends to emphasize glamour over the historicity of beauty, simply because glamour is given to what is transient. Styles are in vogue from one moment to the next, whereas beauty has no time limitation. Glamour exists at the instant the photograph is taken, whereas beauty would appear to hold a mysterious enduring quality that exceeds the temporal limitations of time represented in the photograph. Somehow I get the sense that Hyun-Moh Yang inadvertently understands this.Yet, at the same time, he wants to explore the limits of how design techniques in photography can match the enduring quality of these ancient monuments.

This is a fair question, a question that many artists from many places in the world have tried to surmount, each in their own way. In this respect, I find it curious that Yang limits his intention to pagodas in Korea rather than exploring structures in other part of East Asia as a means of comparison. The subject matter of Shaw’s art is very real. The pagoda is a historic monument, regardless of its scale ? whether small or large. It is a monument that has the potential to extend its meaning beyond a specific religion, yet at the same time is bound to its Buddhist origins and past history.

But again, the photographs of these pagodas by Hyun-Moh Yang are the real issue. The work is not about the pagodas, but how the artist has made the pagodas into photographs. One can look at these images and enjoy their variations and their form. One may visually caress their light and their abundance as being monuments that extend over time for many centuries, objects that have indeed become part of the life and art of the place where they exist. This is would seem the most accurate reason to understand these photographs as significant ? that they pay homage to a history that remains significant even as we look at them today.

Robert C. Morgan (born 1943)is an American art critic, art historian, curator, poet, and artist. He is represented by the gallery Proyectos Monclova in Mexico City.

-

Artist Statement

by Yang Hyun Moh

Engaging in portrait and fashion photography for a long time, I constantly agonized over the kind of photography I truly desired to do. I would meet a model and discover his or her beauty, freeze a moment in a photographic image, and print the photograph to be seen by many. This process was enjoyable for the model, satisfying for the advertiser, and rewarding to me. Through lighting, lenses, and conversations with the model, I would seek the beauty or unique qualities of a subject, which was necessary to get the desired results. To an extent, I found satisfaction in the satisfaction of others. Yet inside, I constantly searched in my heart for the photography I truly wished to pursue. During my studies in Italy, I held an exhibition of photographs of the bright landscapes and ancient ruins of Italy. Fortunately, the images struck a chord with many Italians.

Operating a studio for nearly two decades, I considered the unique beauty of Korea, the distinctive colors and forms of this country. I tried photographing the landscapes and the people of Korea. They kept my interest for about a year, but it faded, and I was unable to continue. As a result, I changed subjects repeatedly. Many countries express their unique cultures in representative images, which foreigners see and remind them of the country. What is that image of Korea? I agonized over finding the answer.

Then one day, I saw a pagoda standing majestically, as darkness set on a ruined temple. The pagoda is in every Buddhist temple we visit, and it is even engraved on a coin. For a Korean, the pagoda is a most familiar object. Yet when I saw that large stonework, it felt powerful and led me to exclaim, “This is magnificent!” How did it survive a thousand years in one place? Why did our ancestors create this? I was curious. I was considerably shocked. Unable to leave the area, I stayed the night at a homestay run by a nearby restaurant. It was a house on the shore, and I could see the Tomb of King Munmu through the window. My room had windows on three sides, and I ended up staying awake for a long time, listening to the beautiful symphony of the waves.

Early the next morning, I went back to the ruins with a camera. The morning air was chilly, and the backlit pagoda looked marvelous, as though it were floating on the horizon. Its greatness struck me with more force than it had the previous evening. I lost myself in the moment, shooting with the small camera that I always carried with me. I took many photographs, from a distance, up close, looking up at it, and from the top of the hill with the sun at my back. Years have passed, but I cannot forget that miraculous moment.

I began to photograph pagodas every chance I found. I started with a small digital camera but later determined that I should capture the great works of anonymous artisans in the largest available size of analog film. I decided against looking up or down at the pagoda, but assumed the point of view from which an ancient artist would have viewed the pagoda. I shot from directly in front of the center of the pagoda to eliminate the distortion caused by the relative distance from the lens. I tried hanging black fabric as a backdrop in order to make the pagoda pop, to show its form, color, and texture in all of its detail. I thought that a subject that is complete in itself will move hearts without any embellishment. Portraits from the Joseon Dynasty “disallow the straying of a single line, or even a point.” Observing this, I photographed my subjects using traditional portraiture techniques. It took about a year to execute these ideas. To line up a large-format camera three to four meters from the pagoda’s center, I built a 4-meter-wide tripod, and connected pipes to hang black cloth in the background.

Most photo shoots occurred around sunrise or sunset, on overcast, rainy, or snowy days. I chose to shoot on many snowy days in particular, because snow eliminated complex elements from the pagoda’s surroundings and allowed me to capture the pagoda more clearly. On rainy days, I was able to show the pagoda more fully because the shadow of the roof stone over the main body disappeared. I used a standard 50mm lens, because it offered angles similar to the range of the human eye, and I could avoid distortion.

Eight years have passed since I began photographing pagodas. I thought two to three years would be enough when I started, but they might occupy me for several more years yet. In the beginning, I was anxious to finish the project quickly, but now I anticipate meeting a pagoda like meeting a lover. I feel excited and happy whenever I see one.

In an exhibition of images of pagodas, shot on 8 x 10 inch film and printed in true-to-life size, a person standing in front of the reproduction will sense the magnificence and beauty of the pagoda, as though facing the real one. I wish to deliver the natural and energetic simplicity and simple yet majestic form that I feel from the pagodas of Korea.

Created by the hands of ancient people who imbued pure-white granite with devotion and faith and built each pagoda carefully, stone by stone, Korean pagodas carried people’s most ardent wishes. After a thousand years, they are still alive, radiating perpetuity and vitality. These stone pagodas maintained a dignified appearance through storms and earthquakes thanks to the devotion and faith of the Buddhists that guarded them. The gothic-style pagoda rises from prayers, meditations, and the mundane world and aims for the sublime. Moving to the higher levels of a pagoda represents transcendence from the mundane world, escape from human desires, and the achievement of freedom and liberation. Looking at a pagoda, the viewer feels peace and jubilation.

Record of Thousand Years

/ Documentary Film of photographer Yang Hyun Moh

-

Hyun-mo Yang’s Pagodas: A Conversation between the Past and Present

by CHOI Jongdeok / Director-General of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage

The pagoda is a Buddhist structure built to enshrine relics that represent the body of the Buddha. The significance of pagodas that have existed for over a millennium is beyond religious. Focusing on this, photographer Yang Hyun-mo reimagines the old pagodas through his own contrivance. Embodying the past and present, the new image is an intersection between the photographer’s intention and the viewer’s imagination.

While these old pagodas continue to be religious objects to Buddhists, the general public views and appreciates them in their own way. Seeing a pagoda standing tall in the middle of temple ruins, some people feel regret as they visualize the pagoda’s glory days a thousand years ago. Others are awe-inspired by the very existence of a pagoda that has withstood the test of time. In the vestiges of time accumulated on the pagoda’s surface, some discover a work of art co-created by man and nature. When I look at an old pagoda, I wonder how one could create such rhythm and proportions using crude and heavy stones, and I am mesmerized by the boldness and inherent sense of balance of ancient people. Through his vision and means, the artist adds another possibility to this wide range of perspectives, allowing the viewer to appreciate the old pagoda in a whole new dimension.

Marvelously, the artist extracts the pagoda from its surroundings, using only black cloth and his camera lens.

Against the black background, the pagoda gives the viewer the illusion that it is floating in pitch darkness in space. From this pagoda, I keenly sense gravity, the universe’s most essential force. This sensation likely derives from a memory of a photograph of black and infinite space, and Einstein’s theory of relativity, which explains how gravity affects space and time and is now common knowledge. When constructing a pagoda, which is significantly larger and heavier than a man, craftsmen of old must have made considerable efforts, whether consciously or unconsciously, to comply with the law of gravity. Any attempt to oppose the law of gravity would have caused the pagoda to collapse, despite the mason’s intention. Black cloth is all that the photographer needs to perform the magic of reawakening that primal force.

Like a black hole, the black cloth hung in the background swallows every disparate element, directing the viewer’s focus wholly on the pagoda. This is comparable to the Zen Buddhist meditation practice of facing the wall and closing one’s eyes in order to gaze at one’s inner self without being distracted by any form of anguish. In the pagoda reinvented by the artist, the viewer reads the true nature of the old pagoda.

Even though not one component remains unmarred, the restrained simplicity and the exquisite, harmonious proportions of old pagodas are cathartic to view. The exquisite adornment of the pagoda facing the seated bodhisattva image is remarkable, elaborate, yet unobtrusive. The bodhisattva, who devotes himself each morning before daybreak to attaining Buddhahood, appears to be reaching nirvana. In the photograph of the snow-covered pagoda, the contrast between the white snow and the black background emphasizes the pagoda’s austere simplicity. The stone brick pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple shows the vestiges of time through each unique stone, which is cut in the shape of a brick. The four lion statues guarding each corner are resolute in their duty to protect Buddhism. I had previously overlooked the component pieces of the pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple, which are similar yet slightly different and come together to create a splendid whole.

In Yang’s work, the black cloth that forms the background is at different times taut with hardly a wrinkle, sagging slightly, or showing a backstitched seam. These coincidences neutralize the effect of artificial intervention in the old pagodas. By the mere addition of a black backdrop, the pagoda images of photographer Yang Hyun-mo plainly expose the years stacked on the pagodas and feed the viewer’s imagination.

-

The Pagoda of Korea

by JUNG Jesung / Director of Korean History Foundation

The pagoda is humanity’s first symbol of spiritual culture.

The origin of the Korean pagoda dates back ten thousand years to the menhir, part of the prehistoric megalith culture. This monumental form evolved into the dolmen, which flourished in the Bronze Age, and about two millenia ago, the Korean pagoda reached its artistic culmination, with a distinctive form influenced by Buddhist culture, which spread from India via China.

The countless pagodas remaining throughout the Korean landscape are of significant anthropological value, as the final manifestation of humanity’s megalith culture. The pagoda is a key element of Korean Buddhist culture, which has long been a part of Korea’s cultural heritage. Its significance is not only in its aesthetic beauty, but also in the fact that for a thousand years, it served an ethnological and historical role, absorbing people’s most ardent wishes, their hopes and dreams.

Even in our globalized, multicultural, contemporary society, seeking the true essence of Korean culture is crucial, and the pagoda is one of Korea’s few pieces of cultural heritage that provide an immediate clue.

Andre Eckardt (1884-1974), the first person to bring global attention to Korean art in the modern era, analyzed Korean pagodas in his book, A History of Korean Art (1928):

Examining a series of monumental towers from all of Shilla [Silla Kingdom] and Koryeo [Goryeo Dynasty] . . . the Korean people of their respective times had a deep and innate understanding of art, and the sensitivity, emotion, true love, and inspiration necessary to make art. These regretfully anonymous artists took the middle path between the art and cultures of the other Far Eastern countries of China and Japan. I believe this to be the fundamental characteristic of the sublime, dignified art of Korea.

Eckhardt praised Korean pagodas highly, writing that the pagoda is the embodiment of key characteristics of Korean art, namely elegant structures without excess, delicate division of decorative elements and lines, and disciplined use of reliefs, which result in natural and energetic simplicity and simple yet majestic forms, which cannot be found anywhere in China or Japan.

The mention of an expert is not necessary to know that the pagoda is a beautiful part of Korea’s cultural heritage. Because pagodas are so familiar in our daily lives, we often pay little attention to them and fail to fully understand their true beauty.

Reflecting our forefathers’ belief in the “Three Realms” of Heaven, Earth, and Man, the pagoda represents Man, who stands between Heaven and Earth. An attribute of the “Three Treasures” of mankind?spirit, energy, and mind?the pagoda alludes to the destiny of the human spirit, born of the Earth and returning to Heaven.

The pagoda is like the flame of the spirit. It contains mankind’s age-old hope to nurture the spirit and, in the end, set it ablaze like a fire reaching into the sky and return to Heaven, the home of our souls.

Look at the pagoda. Circle it a few times. Why do we feel relaxed and peaceful? It is because we are all, at our roots, aliens from somewhere in the sky. Our ancient ancestors called themselves jeokseon, meaning immortals from outer space, who have come to Earth to live in exile.

There is a long-held belief that when we die, we leave our bodies on Earth, but our spirits and souls, which never die, return to our home in Heaven. This longing, handed down from our ancestors and engraved in our DNA, exists deep in our subconscious. Thus, we feel familiar with the pagoda and identify with it, and we often feel the impulse to return to an unknown place.

Hailing from the dim and distant past, we are travelers of time and the immeasurable cosmos. We are comrades in wandering, who will forever repeat the journey home and be born again. Thinking of humanity from this perspective helps us see why our ancestors devoted themselves to building pagodas and leaving them for posterity.

Korean pagodas are milestones and compasses of life and death. They are the open gates to Heaven, the original home of our spirits. They are a flame-like revelation of a spirit that was once buried. They are a symbol of the sublime human spirit, achieved by neatly stacking the transparent and bright energies of the universe.

Photographer Yang Hyun-mo embarked on a long, bold journey to discover the truth of pagodas, which represent the traditional Korean aesthetic. Yang employed a wide range of techniques to project the essence of the pagoda, which no one had tried to see, and succeeded in bringing the viewer face-to-face with the pagoda’s magnificent form and the beauty of its essence, which had eluded our field of vision. I would venture to say that Yang’s work is the one of the boldest and most meaningful fruits since the introduction of modern photography, resulting from the encounter between photography and traditional and cultural heritage.

Yang’s photographs of pagodas, taken from various angles with a wide array of self-discovered methods, are almost fearfully honest. They are hyperrealistic depictions of the spirit, soul, sweat, and sorrow of our artisan grandfathers. They are an open and stunning revelation of the sanctity of Heaven that has descended to Earth. This is the essence, heart, and message of Yang’s photographic art. Viewing his photographs, we can take a moment to linger in Heaven, eat and drink the cosmic energy that the pagoda offers, and indulge in true respite that accompanies spiritual enlightenment and pleasures our hearts.

These pagoda images are Yang’s own way of doing good unto contemporary people, who are suffering constantly, spreading good unto others without lingering, the Bodhisattva practice for the benefit of others.

Not only has Yang Hyun-mo been successful in rediscovering Korean pagodas, he is achieving impressive results in restoring the paragon and icon of the Korean aesthetic.

-

About Pagoda

by Yang Hyun Moh

Look up the definition of beauty in the dictionary:

A pagoda is a tiered tower with multiple eaves, built in traditions originating as stupa in historic South Asia and further developed in East Asia or with respect to those traditions, common to Nepal, China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Myanmar, India, Sri Lanka and other parts of Asia. Most pagodas were built to have a religious function, most commonly Buddhist, and were often located in or near viharas.Location Of Pagoda

Here is the location of each pagoda in Yang's works in Korea. "Visit the beautiful Korean Pagoda and feel the unique atmosphere"

1. Chungungli, a five-story stone pagoda :

465, Chungung-dong, Hanam-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea (465-060)2. Sinleugsa, a three-story stone pagoda :

73, Silleuksa-gil, Yeoju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea(12636)3. Sinleugsa, a Multi-layered stone pagoda :

73, Silleuksa-gil, Yeoju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea(12636)4. Gaesimsaji, a five-story stone pagoda :

254, Dongnam-ri, Buyeo-eup, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea(323-806)5. Jeonglimsaji, a five story stone pagoda :

254, Dongnam-ri, Buyeo-eup, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea(323-806)6. Wang-gungli, a five story stone pagoda :

San 80-1, Wanggung-ri, Wanggung-myeon, Iksan-si, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea(570-943)7. Geumsansa, a multi-layered stone pagoda :

San39, Geumsan-ri, Geumsan-myeon, Gimje-si, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea(576-962)8. Silsangsa Baegjang-am, a three-story stone pagoda :

447-76, Cheonwangbong-ro, Sannae-myeon, Namwon-si, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea(55804)9. Hwa-eomsa dong, a four-story stone pagoda :

539, Hwaeomsa-ro, Masan-myeon, Gurye-gun, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea(57616)10. Hwa-eomsa sasaja, a three-story stone pagoda :

539, Hwaeomsa-ro, Masan-myeon, Gurye-gun, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea(57616)11. Won-wonsaji dong,a three-story stone pagoda :

Gyeongsangbugdo Gyeongjusi Oedong-eub Mohwali12. Seoagli,a three-story stone pagoda :

92-1, Seoak-dong, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea(780-200)13. Bunhwangsa,Monastery stone pagoda :

94-11, Bunhwang-ro, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea(38150)14. Jeonghyesaji, a thirteen-story stone pagoda :

1654, Oksan-ri, Angang-eup, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea(780-805)15. Sunshan Jukjang Dong, a five-story stone pagoda :

90, Jukjang 2-gil, Seonsan-eup, Gumi-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea(39110)16. Sanhaeli, Monastery stone pagoda :

Address17. Hwangbogsaji,a three-story stone pagoda :

78-61, Hwangbok-gil, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea(38175)18. Seoggatab :

1491-28, Yokjiilju-ro, Yokji-myeon, Tongyeong-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea(53100)19. Gameunsaji, a three-story stone pagoda :

55-1, Yongdang-ri, Yangbuk-myeon, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea(780-891)20. Sajabinsinsateo sasaja, a nine-story stone pagoda :

Address21. Woleongsa Temple, a 8 each 9 floors stone pagoda :

434, Cheonghak-ro, Hoengcheon-myeon, Hadong-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea(52319)22. Sinbogsa, a three-story stone pagoda :

403, Naegok-dong, Gangneung-si, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea(210-926)23. Nagsansa, a seven-story stone pagoda :

100, Naksansa-ro, Ganghyeon-myeon, Yangyang-gun, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea(25008)24. Hyangseongsaji, a three-story stone pagoda :

San 24-2, Seorak-dong, Sokcho-si, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea(217-120)

Pagodas, Korean treasures, stood in one place, receiving prayers and wishes of countless people for over a thousand years.Jason J.Kim

Chungungli,a five-story stone pagoda

466, Chungung-dong, Hanam-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Hwangbogsaji, a three-story stone pagoda

78-61, Hwangbok-gil, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Hyangseongsaji, a three-story stone pagoda

San 24-2, Seorak-dong, Sokcho-si, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea

Dabo Pagoda

385, Bulguk-ro, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Wonwonsonsaji, a three-story stone pagoda

Gyeongsangbugdo Gyeongjusi Oedong-eub Mohwali

Sanhaeli, Monetary stone pagoda

391-6, Sanhae-ri, Ibam-myeon, Yeongyang-gun, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Wang-gungli, a five-story stone pagoda

San 80-1, Wanggung-ri, Wanggung-myeon, Iksan-si, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea

Hwa-eomsa, east, a five-story stone pagoda

539, Hwaeomsa-ro, Masan-myeon, Gurye-gun, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea

Jeonghyesaji, a thirteen-story stone pagoda

1654, Oksan-ri, Angang-eup, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Silsangsa Baegjang-am, a three-story stone pagoda

447-76, Cheonwangbong-ro, Sannae-myeon, Namwon-si, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea

Seokgatap

1491-28, Yokjiilju-ro, Yokji-myeon, Tongyeong-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea

Sajabinsinsateo sasaja, a nine-story stone pagoda

1002, Songgye-ri, Hansu-myeon, Jecheon-si, Chungcheongbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Geumsansa, a multi-layered stone pagoda

55-1, Yongdang-ri, Yangbuk-myeon, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Nagsansa, a seven-story stone pagoda

100, Naksansa-ro, Ganghyeon-myeon, Yangyang-gun, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea

Seoagli,a three-story stone pagoda

92-1, Seoak-dong, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Sunshan Jukjang Dong, a five-story stone pagoda

90, Jukjang 2-gil, Seonsan-eup, Gumi-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Woljeongsa Temple, a 8 each 9 floors stone pagoda

434, Cheonghak-ro, Hoengcheon-myeon, Hadong-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea

Gaesimsaji, a five-story stone pagoda

321-86, Gaesimsa-ro, Unsan-myeon, Seosan-si, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea

Sinbogsa, a three-story stone pagoda

403, Naegok-dong, Gangneung-si, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea

Geumsansa, a multi-layered stone pagoda

San39, Geumsan-ri, Geumsan-myeon, Gimje-si, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea

Sinleugsa, a three-story stone pagoda

73, Silleuksa-gil, Yeoju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Hwa-eomsa sasaja, a three-story stone pagoda

539, Hwaeomsa-ro, Masan-myeon, Gurye-gun, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea

Jeonghyesaji, a thirteen-story stone pagoda

254, Dongnam-ri, Buyeo-eup, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea

Hwa-eomsa south, a five-story stone pagoda

539, Hwaeomsa-ro, Masan-myeon, Gurye-gun, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea

Hwa-eomsa south, a five-story stone pagoda

577-55, Cheonwangbong-ro, Sannae-myeon, Namwon-si, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea

Sinleuksa Multi-layered Stone Pagoda

73, Silleuksa-gil, Yeoju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Myojeogsa, eight-coners, seven-story pagoda

174, Sure-ro 661beon-gil, Wabu-eup, Namyangju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Gilsang, seven-story pagoda

68, Seonjam-ro 5-gil, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Goseonji, three-story pagoda

186, Iljeong-ro, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea

Sharing the Unique and Beautiful Story in Korea

Every quarter, we deliver a fresh and diverse assortment of story and information about Korea in our magazine StoryK. Subscribe today to receive our quartery magazine and join in the conversation unfolding within our pages.

HISTORY

HERITAGE

SPRITUAL

STORY

Meet our delightful panel of speakers